Cis-Lunar has always had a special ring to it. When I started diving, the brand was completely unknown to me while Bill Stone, the founder of Cis Lunar, had been diving with the rebreather in caves for 5 years. The existence of rebreathers became known to me 16 years later. The name Cis Lunar was then known only to an exclusive group of Europeans and Americans. The Cis-Lunar rebreathers were therefore an extremely rare sight. It was only many years later when the MK5P was produced in numbers that name recognition in rebreather circles was a reality. Here is the story of probably the highest technologically developed rebreather of its time and perhaps of today!

During the expedition to Huautla’s Peña Colorada (“Red Wall”) cave the team used 72 of the composite tanks to reach the limit of exploration, 9 kilometers inside the mountain. At that point all 72 tanks were expended and had to be laboriously hauled to the surface following each mission. Navy commander John Zumrick, who was a member of the expedition, mentioned in a meeting at basecamp that alternative life support designs existed. Bill Stone subsequently spent three years (1984-1987) researching first the Navy MK16 rebreather and then the NASA shuttle spacesuit PLSS designs before rejecting both as being unsafe for use in the hazardous “overhead” rock flooded tunnels of Huautla (where one could easily be two to three hours from a tunnel containing air) before deciding to invent a mission-specific device. The apparatus that resulted, the Cis-Lunar MK1 rebreather was revolutionary on several fronts. It was the first truly “redundant” PLSS in that it had twin, independent closed-cycle gas processing “stacks” to recycle exhaled air as well as the important distinction of being able to “cross route” gas and consumables supplies while on a mission.

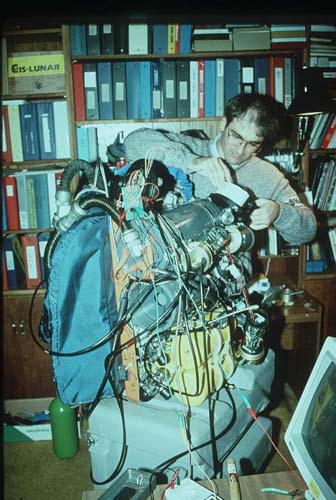

It was also the first diving apparatus to ever use anhydrous lithium hydroxide (LiOH) as its mechanism for carbon dioxide removal. LiOH is dangerous stuff. If it becomes wet the exothermic reaction is so strong that it can produce a steam surge in the apparatus along with caustic chemicals that could severely injure or kill the user. To prevent this Stone designed a hydrophobic membrane separator system. The rig had four onboard computers (two for each half) and a predicted range of 24 hours underwater. On December 3rd and 4th, 1987, Stone (above, reading a paperback in Wakulla Springs, Florida) spent 24 hours continuously underwater with only the MK1 PLSS to keep him alive. Amazingly, the dive was conducted using only half of the consumables available — meaning the MK1 could have been used to remain underwater for two full days.

(text courtesy Stone Aerospace )

1988-1993 MK2 Through MK4

The MK1 testing at Wakulla Springs had shown the amazing promise of a fully-redundant closed cycle PLSS for long range exploration. The “Cis-Lunar” prefix which Bill Stone had given to the device was carefully chosen (and trademarked). The term specifically originates in the aerospace world. At the time Stone was working at NIST on efforts to boost the space shuttle external tank to orbit and to convert it to an orbiting industrial workshop. Working with orbital mechanics calculations daily, he became aware of the term “cis-lunar” which was used to describe the locus in space for the earth-moon system defined by the five Lagrangian stabilization points. It was within this volume of space that the first fledgling commercial manned space efforts were likely to take place. Considering that developing (and using) equipment for lunar exploration was his long-range objective, Stone founded a company, in 1987: Cis-Lunar Development Laboratories, Inc. The MK1 was viewed as a prototype for the type of design one would want in a long range industrial spacesuit PLSS.

Aside from this historical footnote, the MK1 weighed in at 90 kg and was not suitable for terrestrial exploration. Over the following five years three generations of redundant closed-cycle PLSS backpacks were developed and tested, culminating in the MK4 design. This was a 9 hour range depth-independent design with three onboard processors, head-up display, redundant mixed-gas supplies (both heliox and oxygen). It was rated to 200 m underwater and included an integrated real-time decompression engine that was parallel-processed across the three computers. Extensive manned testing included hyperbaric chamber simulations (above, showing, left to right, Ian Rolland, Rob Parker, and Dr. Noel Sloan at the IUC facility on City Island, NY).

1994 San Agustín Expedition

The purpose of of the MK4, and the reason for the sustained R&D effort, was to equip a team for a major exploration assault on the underwater tunnels at -1353 m in the Sotano de San Agustín, on Mexico’s Huautla Plateau. Previous efforts with high pressure open circuit composite systems had reached the limits of that technology in large “going” tunnels. Only a radical technology advance could open that frontier. Equipped with nine MK4 rigs, an international team of 44 explorers, led by Stone, arrived on the Huautla plateau in February of 1994. During the course of the following 4-1/2 months the team explored to a depth of -1475 m (at the time, the 4th deepest point reached by humans inside the planet) and a distance of 7 kilometers from the nearest entrance. Importantly, 600 meters of that distance, beginning at the -1353m level, was through a 30 meter deep underwater tunnel. A total of 22 MK4 missions were conducted during the expedition, many with return-to-safe-haven times exceeding 90 minutes. During the entire project only 1400 liters of oxygen and 2500 liters of heliox gas were used. (Read more at the San Agustín expedition page at the USDCT website.)

The expedition itself was epic in scale and drama. National Geographic Magazine carried a feature story on the project in their September 1995 issue. The MK4 PLSS had proven itself to be remarkably survivable. From a technical standpoint one of the most impressive incidents of the expedition occurred when the lead team of Bill Stone and Barbara am Ende were returning from Camp 6 from the 7-day final push. As they were gearing up and into their pre-dive checklist, the main programmable display on Stone’s MK4 went dead. In the process of descending 92 shafts and traversing 3,000 meters of ropes the rebreathers had taken an incredible beating. The cable leading to Stone’s display had partially unscrewed. This was enough to allow a few drops of water to enter the LCD unit electronics and short it out. This, however, was not the end of the story. After performing a self-diagnostic test the remaining two onboard computers detected the problem, voted the wrist display unit out of the system, and took control. The head-up display flickered momentarily and came up 4×4 green, an indicator that all systems were up and running on automated closed-cycle control. The return dive was conducted without further incident.

(text courtesy Stone Aerospace )

1995-1998 Cis-Lunar MK5 and the Fat Man

The technical success of the MK4 on the San Agustin Expedition attracted both scientific and commercial interest in the following years. The expeditionary MK4 units were used by Bishop Museum in Hawaii to discover more than 200 species of previously unknown fish down to depths of -200 meters in the south Pacific, a zone previously uninvestigated because it was too deep for normal Scuba and too shallow for those paying day-rates for use of research submersibles. It also attracted the attention of venture capitalists. With the infusion of significant capital Cis-Lunar expanded to a staff of 10 and established a manufacturing plant in Massachusetts. It also acquired the underwater communications firm DiveComm and the joint company began a process of developing new products for underwater exploration.

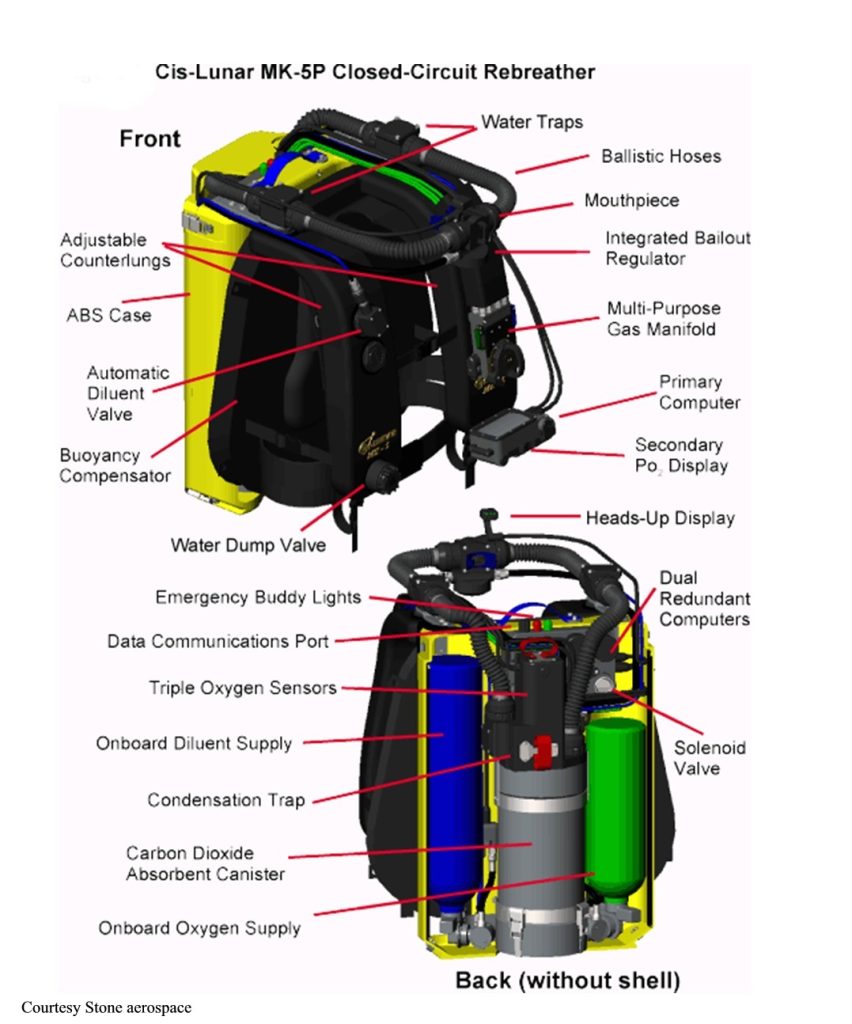

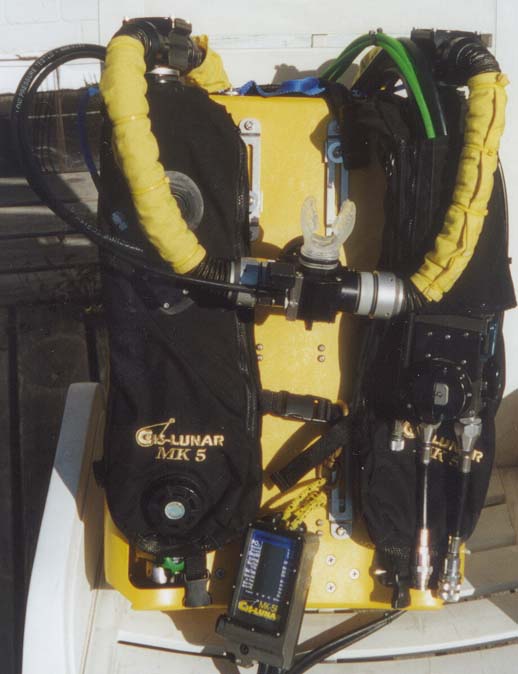

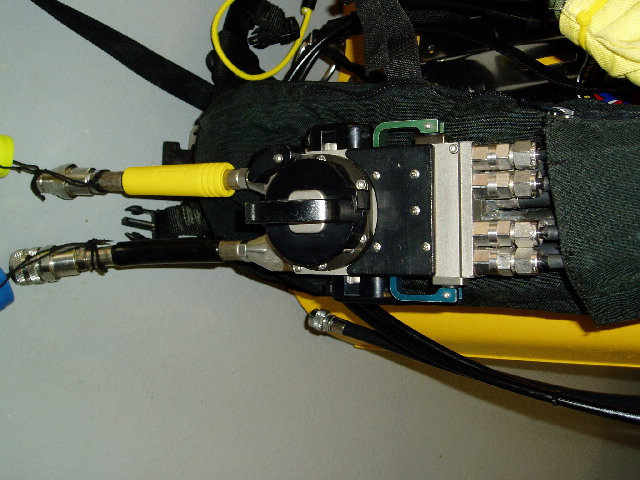

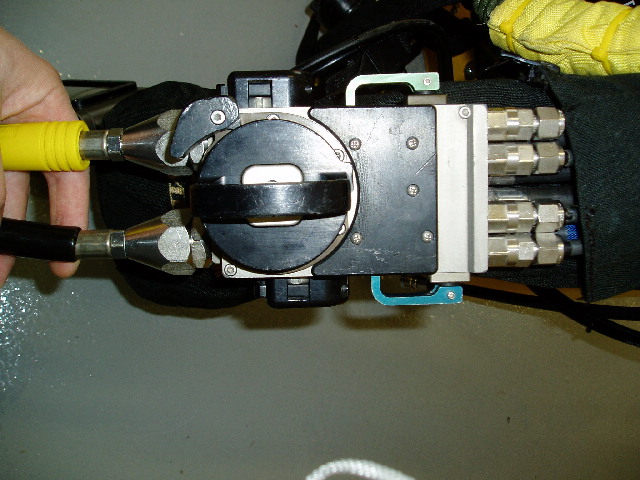

The flagship product was the next generation Cis-Lunar MK5 closed-cycle PLSS. Three years of R&D and advances in electronics and fabrication technology allowed for dramatic improvements in the design, particularly from the user interface, gas routing, and field maintenance standpoint. Importantly, the MK5 was a manufactured commercial product. Through 1999 a hundred units were sold world wide, mainly to scientific, cave, and deep wreck divers as well as underwater photographers, owing to the lack of bubbles and noise. In parallel, a 20 kilometer range underwater propulsion vehicle, known as the “Fat Man” was developed for long range missions to be conducted in Wakulla Springs, Florida in 1999. It used an aircraft alloy hull rated to 200 meters depth and state-of-the-art nickel metal hydride 100AH batteries. It had a variable speed control, a safety kill switch, a backup direct-power switch, and a top velocity of 2.5 knots (1.4 m/s) towing a heavily-laden exploration diver.

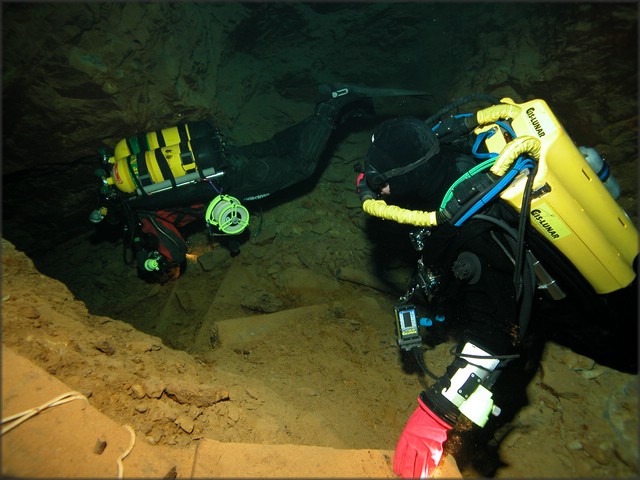

A special dual MK5 was developed for the 1999 National Geographic expedition to Wakulla that had a range of 18 hours. A typical exploration and mapping team (above, at -80m) in addition, carried redundant propulsion systems. This extraordinary combination of technology allowed exploration teams to routinely log missions of up to 5 hours inside the springs. These were at depths of 95m and distances of up to 4 km from the entrance with 2.5 hour return “drives” to return home. They still had waiting of up to 19 hours of decompression. Following the expedition both designs were marketed. Sales, however, were low due to the high cost of manufacture.

(text courtesy Stone Aerospace )

This great article published in Advanced Magazine Issue 4 could be republished with permission of Curt Bowen

Jakub sent me great photos where the MK5 is used in his cave dives and some very nice photos of his MK5P unit. Jakub I am very grateful to you for sharing these photos with us!

Jakub mi poslal skvělé fotografie, kde MK5 používá při svých ponorech v jeskyních, a několik velmi pěkných fotografií své jednotky MK5P. Jakube, jsem ti velmi vděčný, že ses s námi o tyto fotografie podělil!

Therebreathersite was founded by Jan Willem Bech in 1999. After a diving career of many years, he decided to start technical diving in 1999. He immediately noticed that at that time there was almost no website that contained the history of closed breathing systems. The start for the website led to a huge collection that offered about 1,300 pages of information until 2019. In 2019, a fresh start was made with the website now freely available online for everyone. Therebreathersite is a source of information for divers, researchers, technicians and students. I hope you enjoy browsing the content!