The development of the frogman in and before WWII

The Amphibian series of closed diving systems have been developing since before the Second World War. The striking equipment is seen in many photographs and is often difficult to distinguish in its various versions. This page provides information on the origins and implementation of the Mark IV diving systems that were also used by the famous Frogman.

General description:

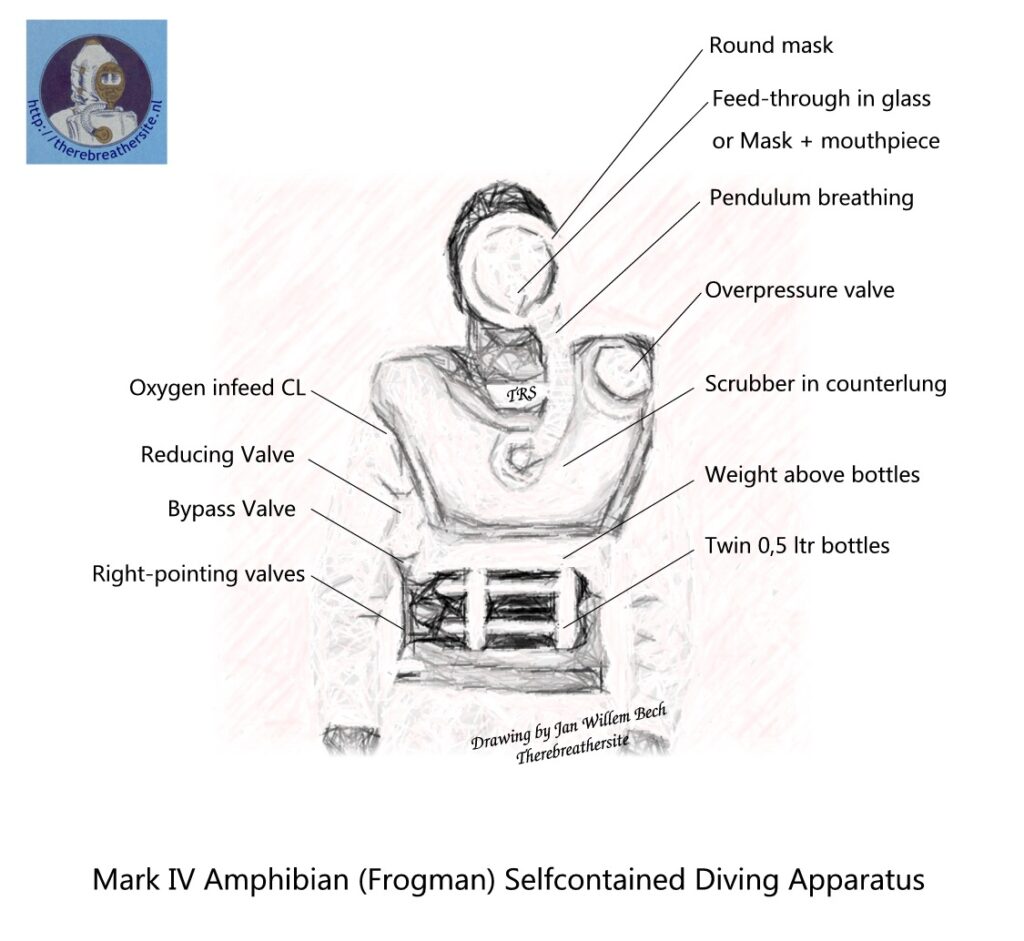

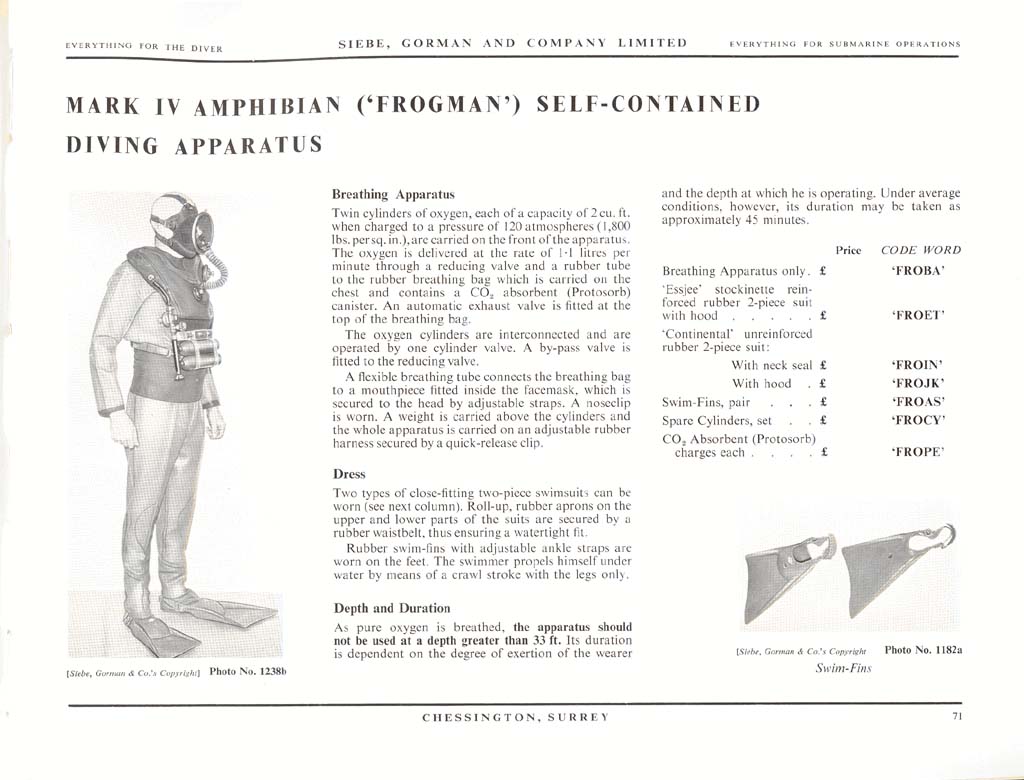

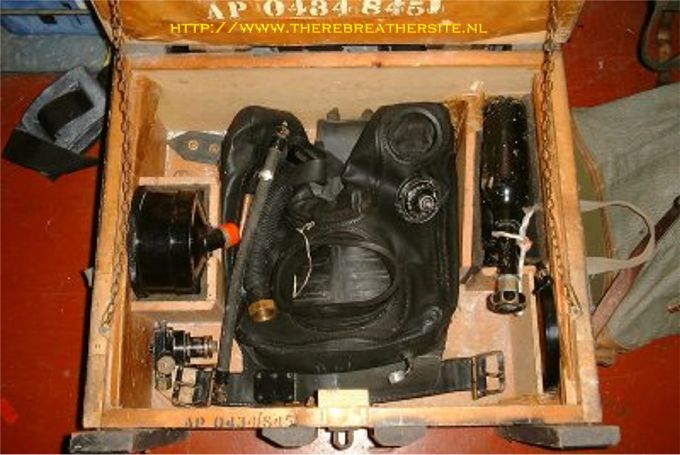

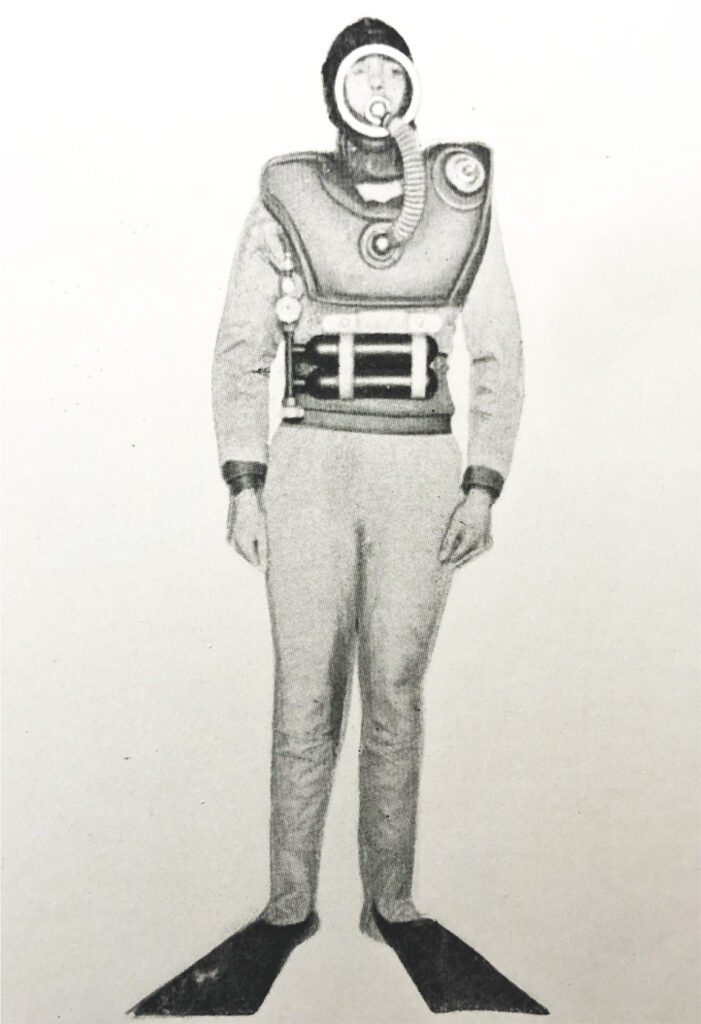

The Mark IV diving set is equipped with two 0.5-litre cylinders with 120 bar of oxygen. There are therefore 56 litres of oxygen available. The manufacturer specifies a dive time of up to 45 minutes. The Protosorb canister is integrated into the chest-worn canister. The breathing hose of the pendulum breathing system is passed through the glass of the mask to a mouthpiece. The same system is also used with normal goggles. The hose is then fitted with a mouthpiece with a shut-off valve. The reducer delivers an oxygen flow of 1.1 litres per minute and can be bypassed with a bypass valve. Excess oxygen can escape through the overpressure valve fitted on the diver’s left shoulder. The diver uses the device with a nose clip so that clearance can still take place with a mask on. According to the manufacturer, the device can be used up to a dive depth of 10 meters with pure oxygen.

“FROGMEN”

(The Development of Underwater Swimming Apparatus)

By Sir. Robert H. Davis

Excerpt from Deep Diving and Submarine Operations

There seems to be a general impression that the so-called “frogman” pedal swimming device is a purely wartime invention. But that is not true. As in the case of so many peacetime inventions which lie dormant or but little noticed, it takes the enterprising spirit engendered by the exigencies of war to bring them to life and into practical use.

Another fiction which has gained currency is that most of the wartime underwater work was done with the “frogman” swim-suit. This is probably due to the picturesque title “frogman”-coined by our newspaper Press with its well-known aptitude for the catchy word-which so caught the public fancy that most of the work done with self-contained diving dresses of .the various types was attributed to the “frogman”. In point of fact, the only things ·unusual about the “frogman” dress are its pedal appendages which give an increased turn of speed and greater maneuverability.

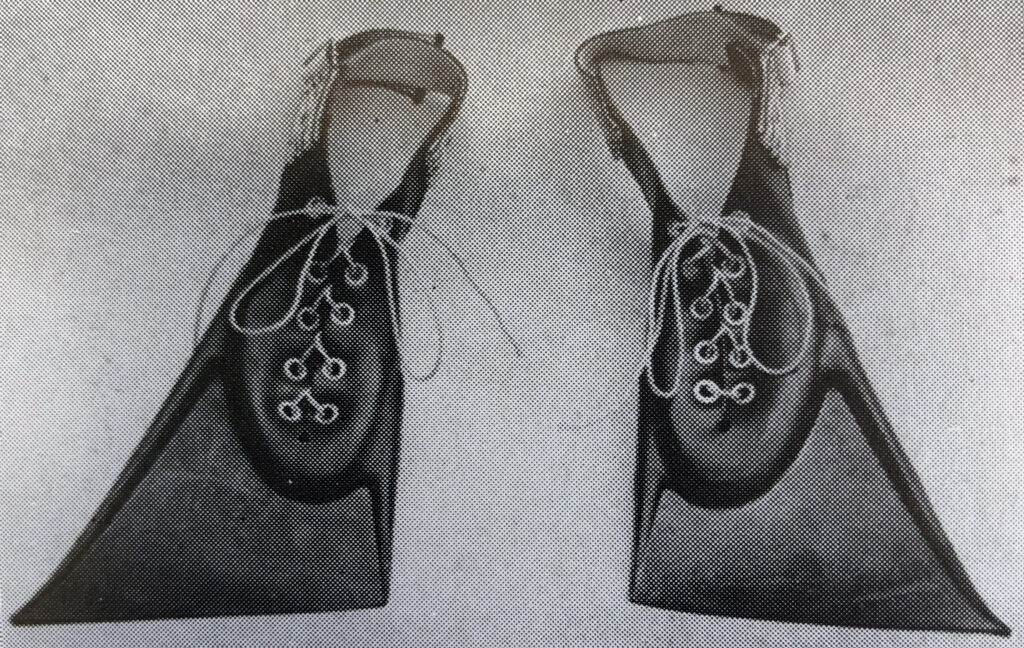

In the 1935 edition of this book (see Part II, Chapter 4 of this edition) we described and illustrated a close-fitting swim-suit with web (frog) feet, designed by the 17th century Italian physiologist and physicist, Giovanni Borelli (1608-1679), a scientist remarkable for s prevision. Their use in the Second World War revived interest in them.

Borelli studied the movements of animals, including man, and likened the working of their bones and muscles to the parts of a machine in producing motion-in other words, the mechanics of their anatomy. His studies of amphibians-seals, frogs, etc.-which, like man, have to come to the surface to breathe, led him to design an apparatus to enable man to remain under water much longer than the unaided swimmer, and, as he says, “to walk on the bottom like a crab, or swim like a frog with his palms and his web feet”. His original description says that the helmet was made of metal, but the Swiss scientist, Bernouilli (1654-1705), criticizing Borelli’s design, rightly pointed out the danger of the rigid helmet owing to the fact that the body of the swimmer, clad in a close-fitting flexible suit of goat-skin, would be subjected to the pressure exerted by the water, while his head in the rigid helmet would be protected from the pressure. Since a plate from Borelli’s book “De Motu Animalium”, published in 1680 after his death, shows a helmet of flexible material, it may be assumed that he himself or his successors had become aware of the necessity for this construction.

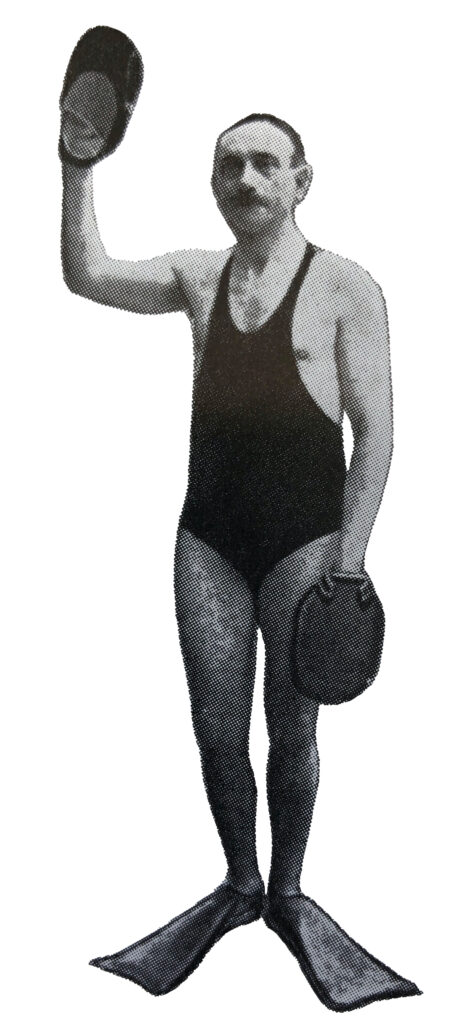

That the Germans, a century after Borelli, had already found certain advantages in the Italian’s idea, is shown by a plate from “Theatrum Pontificale oder Des Schau-Platzes der Brucken und Brücken-Baues”, published at Leipzig in 1726. It must not be thought, however, that Borelli’s idea remained amongst the forgotten things in the interim. As a matter of fact, in the warmer, crystal-clear waters of parts of Southern Europe, Asia and the Southern States of America for many years up to the outbreak of war, the use of rubber “frog-feet”, developed by a French inventor, de Corlieu, in submerged and surface swimming at bathing resorts was a popular pastime with both men and women. Many of the swimmers were also equipped with a simple breathing mask connected via a reducing valve to a cylinder of compressed air, enabling them to remain submerged for a relatively long time.

Some also indulged in the sport of fish spearing with a special type of gun. With the return of peace, these submarine pastimes have been resumed. Doubtless they would also have become popular at our own bathing resorts had climatic conditions been more favourable.

Image 8, taken before the war, shows a French swimmer wearing “frog-feet” and an additional aid in the shape of what we will call “paddle-palms”. Borelli, it will be remembered, refers to the palms in his description.

In the late war, rubber web-foot propellers were worn by combatant swimmers on both sides, in conjunction with close-fitting watertight suits and breathing apparatus on the well-known principle, using oxygen and CO 2 absorbent, originally designed by H. A. Fleuss in collaboration with Siebe Gorman & Co., and adapted by them to various forms of breathing and diving apparatus during the past 70 years.

The swim-suits with frog-feet used by the Germans in the late war were actually made for them by the Italians (Image 9): this would seem to be in the fitness of things, since Borelli, the original designer of the device, was an Italian.

The obvious objective of our efforts to equip divers with lightweight mobile gear must be to make men as fish-like as possible. In the “Human Torpedo” breathing set we had succeeded in making men completely self-sufficient under water for a number of hours. No surface supplies of gases were needed to maintain the diver’s life, nor was there any need for ventilating gases to escape into the surrounding water. The “Human Torpedoman’s” dress was indeed close-fitting and light compared with the standard diver’s 180 lbs. of equipment, and the mobility of these men was remarkable. Nevertheless, they still did their work in the erect position, using their arms and legs for walking and climbing like land animals, and were hardly able to swim at all.

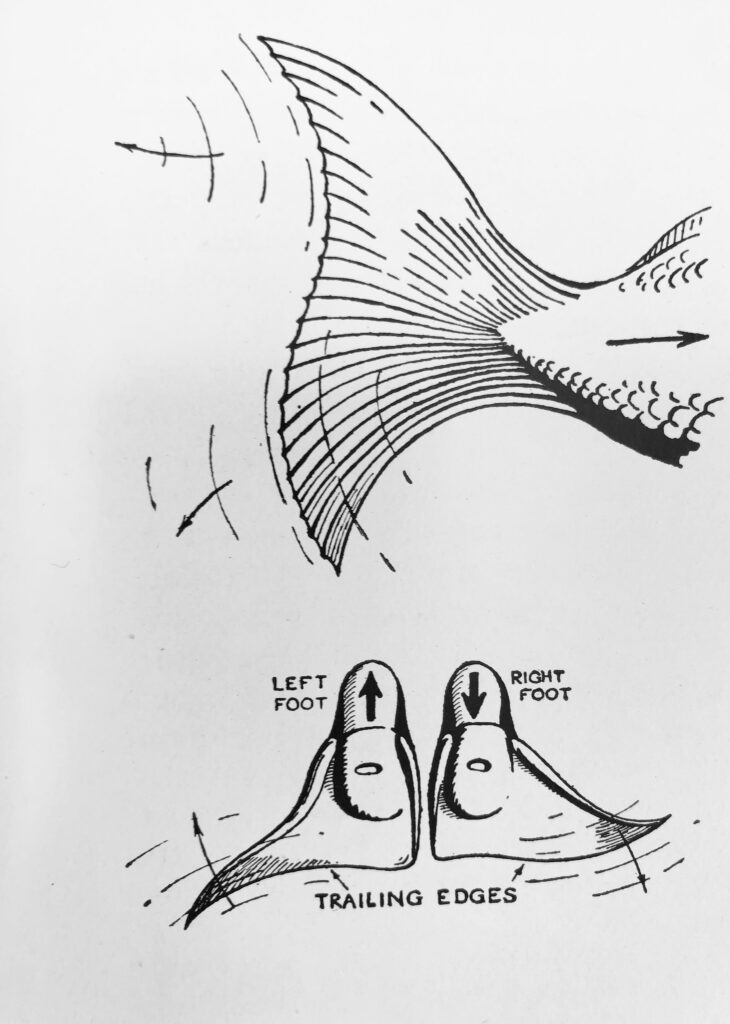

The use of “Swim-fins” or “Frog-feet” immediately converts ordinary man into a swimming creature, giving him amazing control under water, and power and endurance beyond that of even the most powerful human swimmer. The earlier crude versions were usually some form of board or paddle strapped to the feet, and some-times to the hands as well. In its modern efficient form, the “swim-fin” is scientifically designed and moulded from rubber to be fitted as a natural continuation of the foot and ankle. Nothing is worn on the hands, and in fact the hands are not used in underwater swimming at all.

Before going further we must understand the action of fin-swimming. The name “frogman” is a misnomer, since the frog swims with a breast-stroke kick, expanding the webs of his feet for the power stroke., and contracting them for the recovery. Rubber fins cannot be made to “feather” like this, so that a human “frog-man” would make no progress with such a stroke. The design of Image 9; the fins is such that by using the up-and-down beat of the crawlkick., the driving motion of a fish’s tail is reproduced (Image 10). A fish derives all its forward motion from its tail, and only uses its fins to steer and steady itself.

The introduction to this country of underwater swimmers in their present guise, was brought about by Lieutenant-Commander Bruce Wright, R.C.N.V.R.

Wright, a long-distance swimmer and spear-fisherman of considerable experience, put forward a scheme for using the whole spear-fishing technique and much of the gear for underwater sabotage. Colonel Hasler, then serving with Combined Operations, was developing small raiding forces using canoes and surface swimmers, and immediately saw the advantages of underwater swimmers in conjunction with such forces. Thus, early in 1943, the idea was brought to the Admiralty Experimental Diving Unit for the design and development of the necessary equipment to implement the new scheme.

Once again, the problem of protecting the divers against extremes of cold was prominent, and some sort of streamlined close-fitting suit had to be developed to cover the diver from head to foot. Spear-fishermen in sub-tropical waters are amply dressed, in fins, goggles and trunks; such clothing is hardly adequate for Northern European waters.

Experiments quickly showed that existing designs of lightweight suits were unsuitable because they were made of non-stretch material. A suit which is inelastic must be made large enough to allow the diver to dress, and once dressed, to move about without restriction. Under water, the spare material collapses in folds upon the wearer’s body, and the folds set up a resistance to swimming through the water, which cannot be tolerated for long. These folds also trap air in small pockets, and thus give unnecessary buoyancy. This buoyancy can only be overcome by adding. ballast weights and no swimmer can give of his best with lead weights hung about him.

To solve the problem, the assistance of the Dunlop Rubber Company, with its large range of rubber manufacturing techniques, was enlisted. Mr. W. G. Gorham, manager for that company’s Special Development Section, put all his energies and experience into the task.

The suit developed was the prototype of the now well-known range of underwater swim-suits .. Made of rubber spread upon stockinette, fitted with lightweight Latex rubber cuffs and Plimsoll rubber feet, it is entered by a 4-inch hole in a special, highly stretchable, but almost untearable rubber- neck yoke. The entry hole is sealed by clamping on a lightweight tight-fitting Latex hood. The whole suit fits almost like a second skin, giving protection against cold and abrasion, yet having sufficient stretch to allow the diver free movement under water.

With the development of the suit came the usual call for accessories, and ancillary gear to use with it. Most important of all was the need to design and establish the manufacture of “fins”, since without them the suit and other equipment could not be satisfactorily tried out. In 1943, no “swim-fins” were known to be in existence in Great Britain. The only clue to their construction lay in some photographs in an American a publicity swimming pamphlet. pool, In wearing this a fins on Hollywood the wrong beauty feet! was However, depicted, samples draped of over fins the were edge sent of for from America at high priority. Unfortunately, the first consignment was sunk by a U-boat in mid-Atlantic, and trials had to be started with a crude set cut from heavy sheet rubber. Finally, a second batch of samples arrived safely.

The hood and face mask were a fine example of “Latex-dipping” technique. Several models were made incorporating hood and mask in one. But operational requirements called for a mask which could be slipped on and off in the water, to enable the swimmers to take a “look-see”, and get their bearings. The final design of the flanged joint between mask and close-fitting hood was an excellent example of the rubber-worker’s skill.

Before the final suit was evolved, many other details had to be worked out and put into production. These included special zip-fastened undersuits, goggles, “swim-shoes”, and camouflaged caps for “naked” swimmers. Whole suits in camouflage, and even different coloured fins, as well as a large range of test and maintenance equipment were required.

Thus the British “frogman” became the best equipped in the world. His rivals on the Axis side used an Italian designed suit of thin black sheet rubber, finishing at the neck. Though very light and easy to wear, such a suit gave no cold protection and was easily damaged.

Underwater swimming calls for a new diving technique unlike anything used before. The swimmer is horizontal in the water, instead of standing or crouching; he frequently dives down head first, and his leg muscles are in constant action; he swims with his legs alone, with his hands free to operate his breathing set or to steady and guide him. In fact, the Italians refer to their swimmers and human torpedomen as “sommozzatori” or “plungers”.

The swimmer must have absolutely neutral buoyancy; any weight he carries must not be on his neck, shoulders or feet, but exactly in the middle of his body. In fact, he is like a submarine. If trimmed too heavily, he will sink slowly to the bottom. On the other hand, if too light, his feet will come up, as he strives to drive himself down against his own buoyancy, and he will end up by kicking fruitlessly

on the surface, splashing violently and making no progress at all.

Depth and direction-keeping are difficult. Swimmers usually wear a wrist compass to guide them to their target, but they have to learn to steer by natural aids such as by keeping sun or moon on a definite bearing, or by coming up for quick looks at their surroundings.

Depth-keeping must come almost entirely by training, and the swimmer must learn to judge his depth by feeling the pressure changes on his ears, the temperature gradient of the water, or by the appearance of the surface above him, or by the sea-bed below.

All these requirements mean that special care must be given to the design of the breathing set. It must be designed so that the essentially heavy items such as cylinders and reducers do not upset the delicate balance of the “frogman”, and it must give comfortable, effortless breathing in any and every position that the diver may assume.

Siebe, Gorman & Co.’s “Amphibian” Mk. III and Mk. IV, Dunlop’s Underwater Swimming Breathing Apparatus (U.W.S.B.A.) and the Admiralty “Universal” are all designed with this end in view. The design of the breathing system is based upon confirmatory work done at the National Institute of Medical Research for the Admiralty by Doctors Sands and Paton.

These workers determined the maximum resistance, expressed in terms of millimetres head of water, which could be tolerated by divers in all positions under water without interference with normal respiration. The ideal position for the breathing bag relative to a diver’s ear was named the “Eupnoeic depth”, and it was shown how this depth varied with the depth of respiration. By designing the breathing set so that the “Eupnoeic depth” is never exceeded under any conditions, the best breathing conditions possible are obtained.

In the course of the development of these sets, the first trials of the “frogman” gear, and indeed the early training of the operational teams, were not without incident. It seemed that underwater swimmers were unduly susceptible to a phenomenon known as “Shallow Water Black-out”. This black-out had been experienced occasionally before by other oxygen divers, but never so frequently as by the “frogmen”. Many theories were put forward and remedies tried, but the true answer was elusive.

This trouble took the form of temporary mild unconsciousness and mental dissociation, and occurred at depths too shallow to be attributed to oxygen poisoning or other causes due to pressure.

Dr. Kenneth Donald, o.s.c., M.D., of the A.E.D.U., demonstrated that men breathing a high percentage of oxygen did not appear to receive the normal warning of the onset of CO2 intoxication. In other words, the respiratory center was failing to react or to take the natural precaution of hyper-ventilation. Simultaneously, it was shown that the oxygen uptake of underwater swimmers is far in excess of that of arty other type of diver. For instance, while an ordinary diver carrying out the recognized hard work of a fast search over rough and muddy bottom, may consume 1·75 to 2 litres of oxygen per minute, a “frogman” doing a fast length of a swimming bath, will use as much as 3 to 3,5 litres per minute, in spite of the apparently easy swimming motion. This additional consumption is probably due to the constant action of the heavy leg and thigh muscles, and a correspondingly high rate of CO2 evolution results. Thus the underwater swimmer was unsuspectingly pouring out carbon-dioxide into apparatus designed to normal standards, and to make matters worse nature’s defensive mechanism against CO2 intoxication was failing to function correctly.

So much attention has since been paid to the design of canisters, to the composition of CO2 absorbent materials, and to the elimination of dangerous “dead-space” that “shallow water black-out” is becoming a rarity, and if it occurs now it can nearly always be attributed to defective or badly maintained equipment.

This, then, is the ” frogman” equipment of which so much has been heard and with which so much has been achieved. The development was again a “top secret”, high priority, achievement, to which the best available industrial and scientific resources were harnessed.

In war, the “frogmen” carried out sabotage operations against enemy shipping, and counter-sabotage de-fence diving, searching for “limpets” and infernal machines which may have been attached to our ships by enemy divers. The biggest scale users, however, were the Landing Craft Obstruction Clearance Units-those teams of courageous young men who leapt into the sea ahead of our invading troops off Normandy, Holland and Burma, and, swimming under water, blasted great gaps in the enemy’s bristling hedgehog defences on the beaches, thus allowing the first waves of landing craft to sweep in and discharge their cargoes of fighting men and vehicles.

Now, in peace, the “frogmen” have turned their efforts to a host of different pursuits. “Cave-divers”, who explore the underground caverns and rivers in the limestone hills of Great Britain, have adopted “frogmen” methods for penetrating flooded chambers. Another group has adopted the technique for minor repairs to damaged ships, and the rapid survey of sunken wrecks in shallow water. A young scientist on an Antarctic whaling expedition, used “frogman” gear to dive under the great carcases of whales to record their body temperatures and other data.

So man’s challenge to the world of fish and other marine creatures grows with every fresh development. The “frogman’s” speed and agility and his independence of bottom . conditions give him many advantages for certain types of work in shallow water.

Although there will always be work under water which requires other, and heavier, equipment for its proper fulfillment, and while there are operations of war for which the normal “frogman” may not be properly equipped, nevertheless underwater swimming is now recognized as a serious form of diving, whether it be for war, for the routine work of peacetime, or for sport.

Therebreathersite was founded by Jan Willem Bech in 1999. After a diving career of many years, he decided to start technical diving in 1999. He immediately noticed that at that time there was almost no website that contained the history of closed breathing systems. The start for the website led to a huge collection that offered about 1,300 pages of information until 2019. In 2019, a fresh start was made with the website now freely available online for everyone. Therebreathersite is a source of information for divers, researchers, technicians and students. I hope you enjoy browsing the content!