It is a pleasure to add these pages to my homepage. The Innerspace “Porpoise Pack 1” has undoubtedly much more historical and design criteria I could ever mention here. Nevertheless it is an incredibly high tech unit for it’s time. We are talking 1974. Innerspace is testing a system based on the Biomarine CCR 1000 from the Biomarine Industries in Devon. The unit was brought by Mr. F. Parker involved in the development of the rebreathers used in the Apollo program. This information could only be presented with the help of several persons, starting with the great help of Mr. Vance A Johnson, test diver of the unit. Permission for this publication was given by Leon Scamahorn of Innerspace, and unbelievable effort was put into this report by Stefan Besier! He photographed the unit recently and added his professional comments to the photos. The equipment made available for photos courtesy of Pete & Sharon at Steam Machines Incorporated I want to thank all mentioned people for sharing this important information with us. Since there is a big gap between the development of the Electrolung and the latest units such as Inspiration, Prism, Kiss and Megalodon, I am very happy to fill in a bit of history here.

The pages published here are sometimes difficult to read, they where scanned, collected, and almost 30 years old. Also the download time is considerable since almost 50 photos are offered. It’s worth waiting for!

I hope you enjoy reading these pages,

Janwillem Bech.

The Rebreather Invasion

by

Leon P. Scamahorn

(Shadow diver)

© 1996 by Leon P. Scamahorn. Reproduction and distribution, in whole or in part, is authorized provided credit is given to the author for the content.

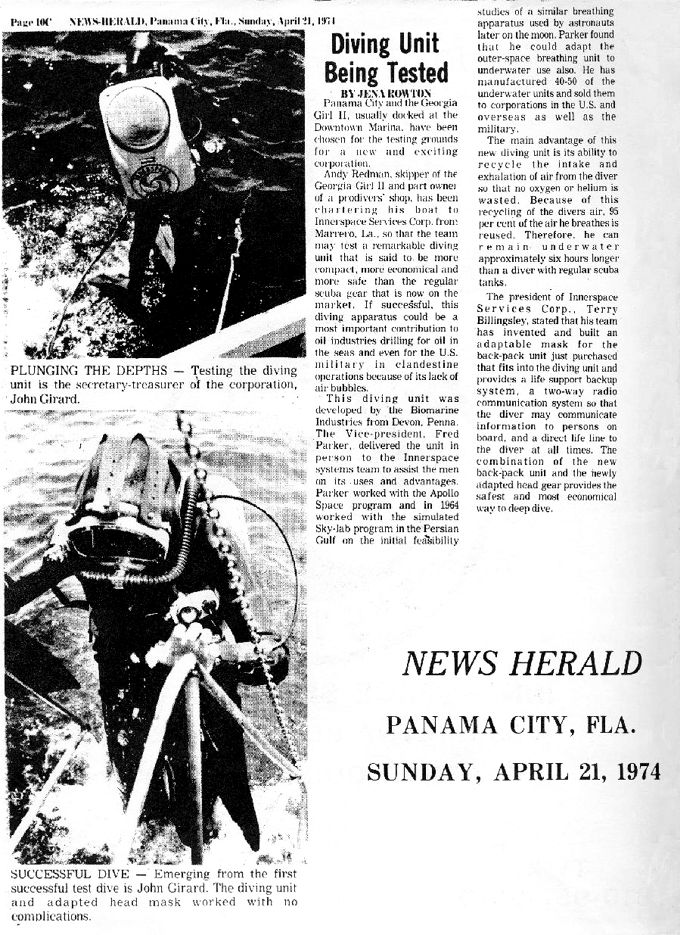

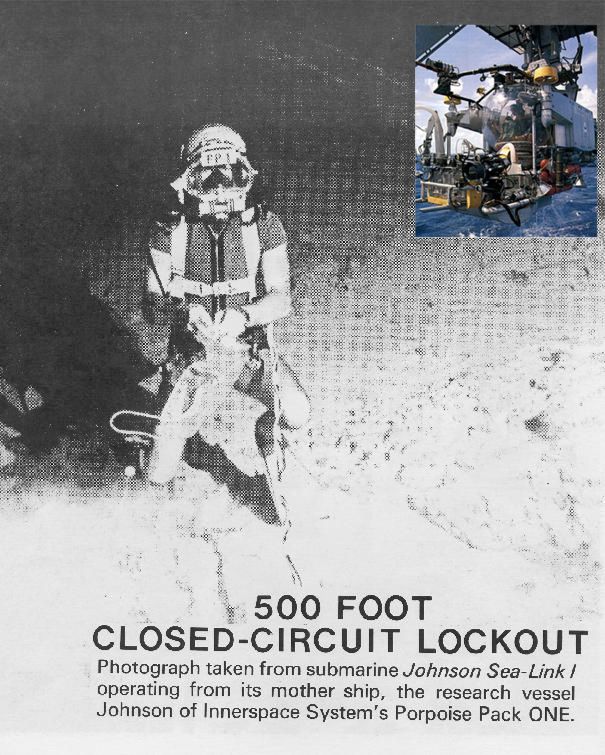

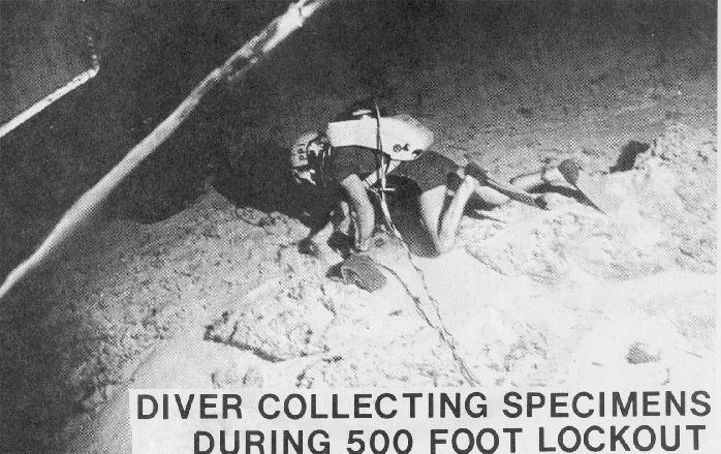

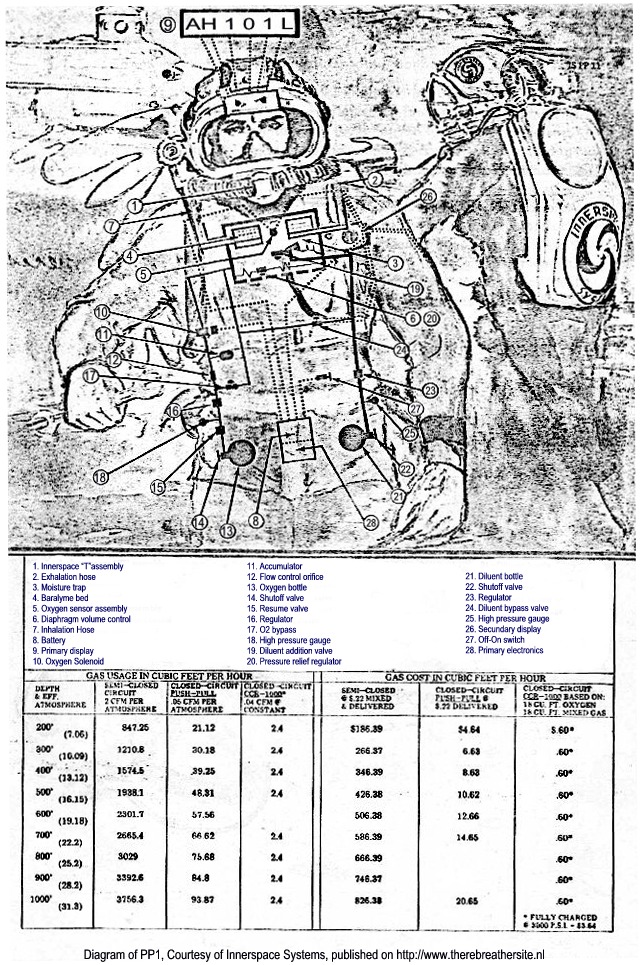

In the sixty’s aerospace technology revolution was on. The race to the moon and the technology supported it. While man was focusing outward toward the stars there were a few aerospace engineers looking inward, “innerspace”. The technology being developed to support Astronauts was also compatible for marine exploration. Gas tight zippers, high-density waterproof materials, electronics, plastics, high and low pressure regulated pneumatic plumbing, efficient CO2 scrubber breathing systems and small galvanic oxygen sensors made advanced diving systems possible. As in the aerospace industry, another race was on to develop innerspace life-support systems that would support a diver at any depth for a great length of time. Driven by Uncle Sam for military application and offshore oil companies, systems were developed to support those types of mission driven applications. One system in the latter sixty’s rose above the rest. With the current technology at that time the system capability was impressive, six hour duration at any depth rated for a maximum depth of 1000 fsw.(2000 fsw for saturation using passive and active thermal heating systems.) The US Navy Experimental Diving Unit tested the system. They found the breathing qualities and system integrity was second to none at the time. The failure analysis on the research & development program exceeded most fighter aircraft of that period, and has been the U.S. Navy’s mainstay for almost two decades. With an accumulation of over a million manned diving hours. The system was a modified Bio-Marine CCR-1000 Called the Innerspace Porpoise Pack one, a highly efficient and robust system that had no equal, and at this current time systems as old as 20 years are still in operation.

The design criteria for the system was:

- Complete autonomous diver operations without umbilical or surface support.

- Depth advantageous of mixed gas, such as minimal inert gas narcosis.

- No tell tail bubbles.

- Acoustically invisible.

- Maximize gas conservation.

- Increased overall safety.

- Capable of inert gas switches and oxygen Partial Pressure manipulation to reduce decompression.

The commercial dive industry was interested in maximum gas conservation and maximum diver productivity. Gas consumption at 1000 fsw ran about $3,756.30 per hour, not including paying the diver and support equipment.

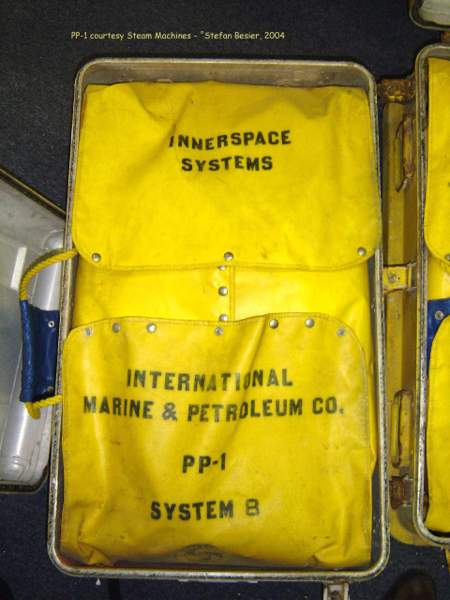

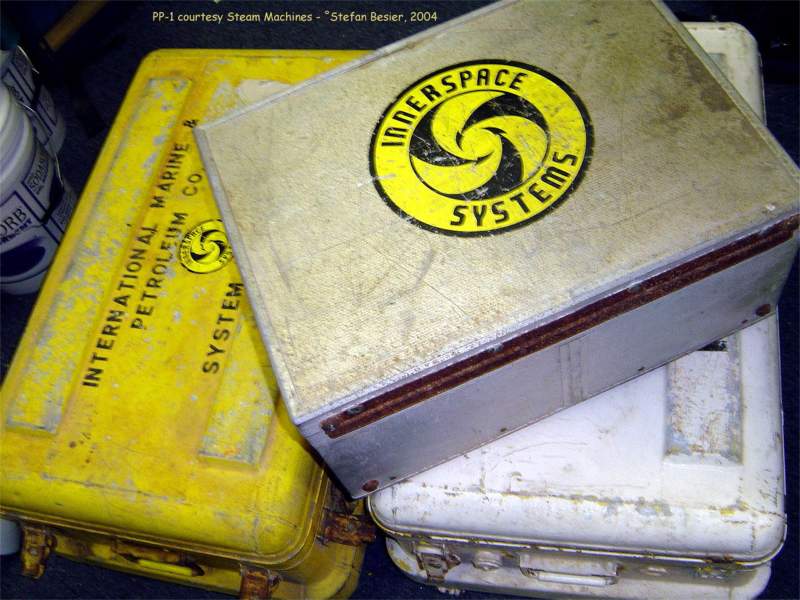

Here are three units with consecutive serial numbers, 350-352. They each have their own (very) heavy duty steelcase with thick custom soft carry bag.I’ll show them in the order I photographed them, helmets first, then the rigs, and finally the spare kits.As you can see, there is a separate metal case for the helmets, which in also each have their own soft carry bag. The bags are color coordinated with the ones for the rigs and are made from the same heavy duty material. Innerspace’s logo is on the inside, and the bags are perfect fits.The helmets were contracted from Aquadyne and then adapted for the use with the PP-1. Solid, commercial hardware. (note Janwillem: the helmets where a model Aquadyne DMC 7 adapted to fit the PP-1)

The rigs in their transport metal cases, wrappedinside the padded soft carry bags. Very well done.As you can see, these were owned and used by theInternational Marine & Petroleum Companyfor commercial oil work. Which explains the raggedlook, they were working rigs.

(What about this very early hammer head ? 🙂 ))

The box that contains the battery on top and has the analog electronics on the bottom. Also the primary wrist display with its warning lights. (Alarm – Low pO2 – 0.1 below setpoint – On setpoint – 0.1 above setpoint – High pO2)

Finally two secondaries side-by-side. The yellow one was originally used with the PP-1s, but they had problems

with the material and switched to the black display made from different material.

As you can see in #710, the PP-1 had a solid handle, and screw on caps to close the loop when removing the hoses.

Two items frequently missing on modern rebreathers. The two contends gauges even have a tie-down for transport.

Here two pictures of the rig standing up. You can clearly see the simple, but heavy duty harness, and the equalizing holes in the case that allow the counterlung to move. On the side metal latch and manual add button. In frame 713 you can also see the power switch next to the D-ring on the case (diver’s left side). #716 with the cover removed. The flasks are steel, between them on the bottom the space for the electronics module.In the upper space between the flasks is the solenoid, above the accumulator. Underneath the flasks is the ss pipework with filters and manual add valves.

The center section, undeniably the best and most unusual design feature of the PP-1, MK series and whatever othername they marketed by. 718 shows has just the locking nut removed, the sensors holder is visible in the center behind the cover. The white ‘holes’ in the metal scrubber housing are scrim covered ports that allow the gas to flow through the scrubber. Exhalation hose mounts left, inhalation on the right side. 720 has the little cover removed and shows the sensor array. No sensor face is on the same plane. 721 is the canister side of the center section with the scrubber removed. On the top left the port that allows exhaled gas to enter. From here it passes through the before mentioned ports in the canister through the scrubber bed. 719 again shows were the scrubbed gas exits the canister.The heated, moist gas hits the metal dome, against which it condensates. Here the gas flow is split, some of the gas is routed through the gap between the canister and the housing into the counterlung. The rest flows past the sensors where the amount of O2 is measured. Between the condensation on the dome and the reduced amount of gas (and hence of moisture) sensor condensation is not a problem for this rebreather.

Here two more views of the axial annular scrubber. #726 shows the fairly shallow but very wide container.As well as the fill port, that is also seen in #725. This is one of the drawbacks of the 15’s design, the small opening makes filling the scrubber (as well as dumping wet absorbent) very inconvenient an relatively time consuming.The other two shots are overall shots, with # 724 showing one of the support cases in the back.

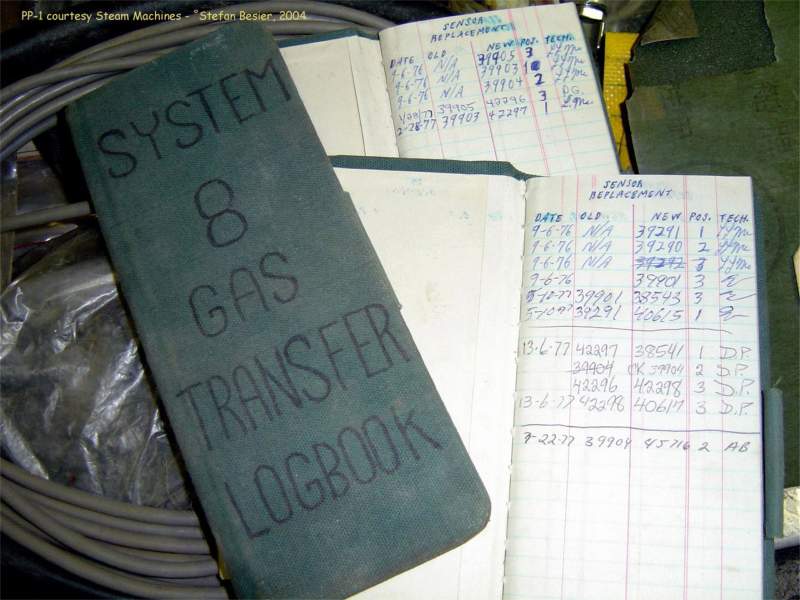

#728 – the two PP-1′ s packed in there riged cases. Did I mention I really like the cases and bags?#731 – shows them again, with one of the two support cases. As well as the Innerspace logo, which, like the name, is still used by the company that manufactures the Megalodon today.# 733 & 734 – are the original log books of the two units. System logs, not dive logs, showing sensor replacement and maintenance. Even the gas transfer log is still available. Not bad for 27 year old systems!

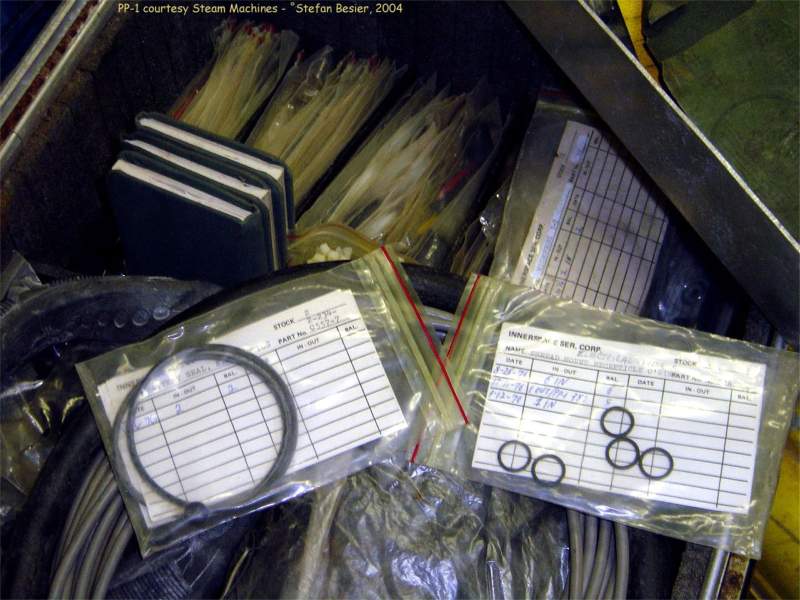

Here are some pictures of the supply cases.# 736 is one of the two. It has a complete set of tools (735) mounted in the lid. The tool set folds forward on a strap or down entirely. Behind it is space for tables and paperwork. There you’ll also find the yellow flags to write you deco plan on, as well as note pre-dive notes like calibration etc. (732) All color coordinated of course, when they sold this as a complete system they mend it. As you can see in the close-up (#737), the case is full with spares, cables, wires, seals, screws … just about anything you could possibly need. Including an original spare battery.

The battery is a Duracell, shaped so that it will fit into its compartment on top of the electronics. (738&739) Batteries were sold for $38.95, sensors cost $180 each. Those are from an original spares price list, a replacement secondary (the analog one) cost $931.10 The final two shots are of the second parts case, which holds two additional steel flasks, wrapped of course), as well as hoses and additional spares like the battery cap that’s shown.Even seeing the way that the PP-1 systems were really configured as a very complete system the original price of around $30,000. (especially in 1975) would have been a very high price to pay for private divers.

A final word about the photos. Since the download time has to acceptable I had to change the resolution and size of the original pictures. I can assure you that the original quality is fantastic! All photos were made by Stefan Besier.

first publication 31-08-2004

Therebreathersite was founded by Jan Willem Bech in 1999. After a diving career of many years, he decided to start technical diving in 1999. He immediately noticed that at that time there was almost no website that contained the history of closed breathing systems. The start for the website led to a huge collection that offered about 1,300 pages of information until 2019. In 2019, a fresh start was made with the website now freely available online for everyone. Therebreathersite is a source of information for divers, researchers, technicians and students. I hope you enjoy browsing the content!