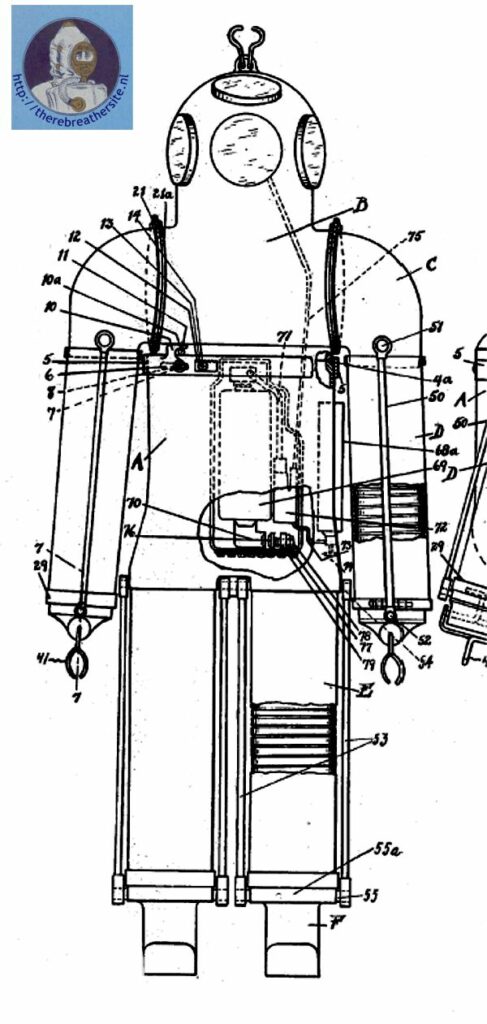

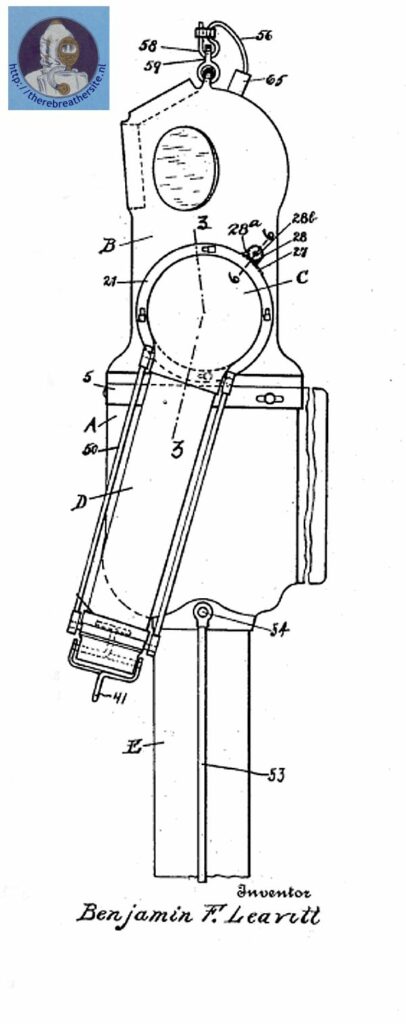

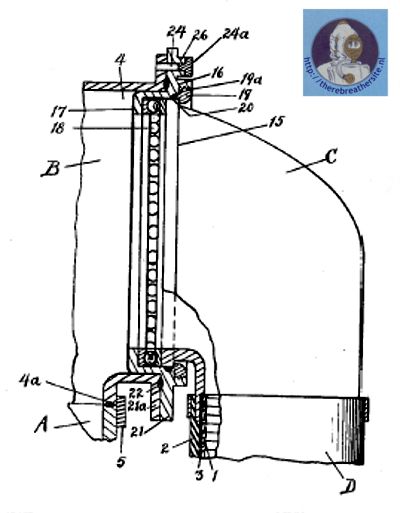

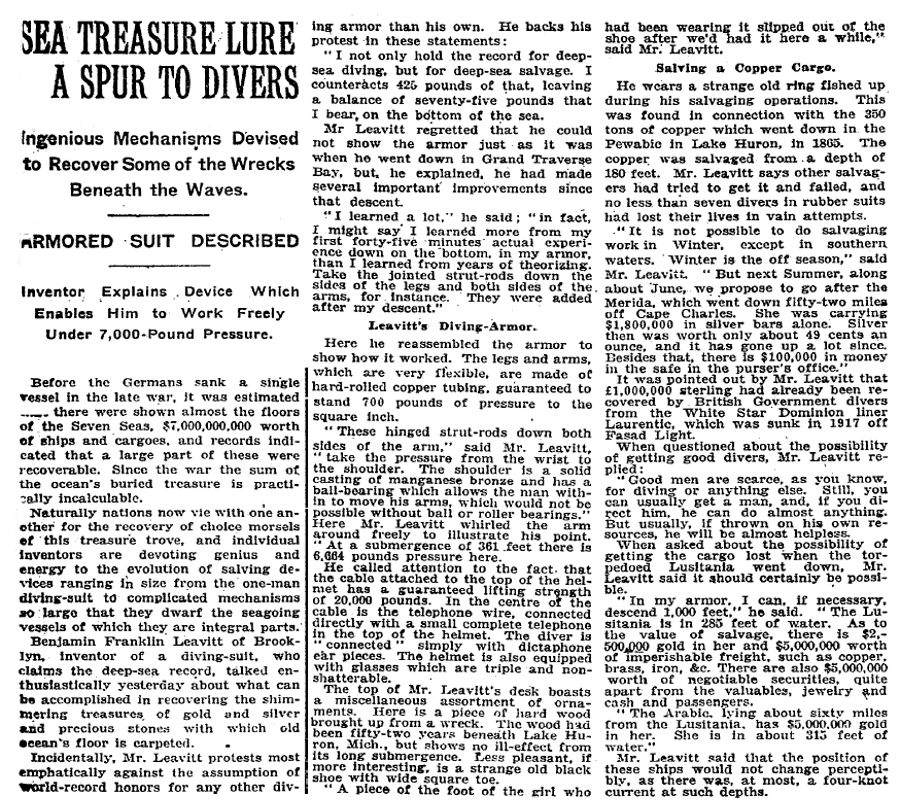

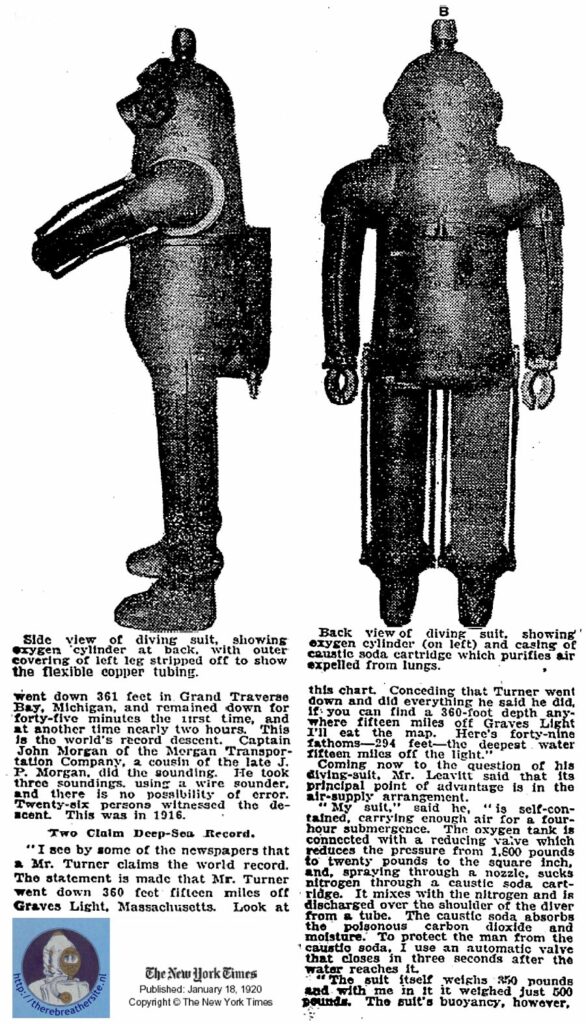

Benjamin Franklin Leavitt build another revival of spiral armouring like Buchanan and Gordon. The radius pieces of the flexible arms and legs add to the resemblance. In this case, however, the spirals form both armouring and covering, after the fashion of a flexible metallic voice pipe. Its utility under heavy pressure is questionable. The air supply is self contained.

Al information about Leavitt and his Salvage company shows that Mr. Leavitt seems to be more a commercial man than an actual diver. The stories written about him are all about money, and many times when the moment of truth was there, plans were changed. In the book of Gary L. Harris ” Ironsuit ” you can find detailed information about the man. ( ISBN 0-941332-25X 1994).

Although many stories are in a way negative, Leavitt had patents, a salvage company, an actual build a atmospheric suit and an undersea lamp. (building the actual suit is a rare practise in the world of atmospheric diving science. Most suits where build in the minds of great inventors 😉 )

He managed to be in the news many times and was very successful in getting famous with his stories. Many people invested in his projects.

Leavitt patent for his diving suit: US Patent 1327679

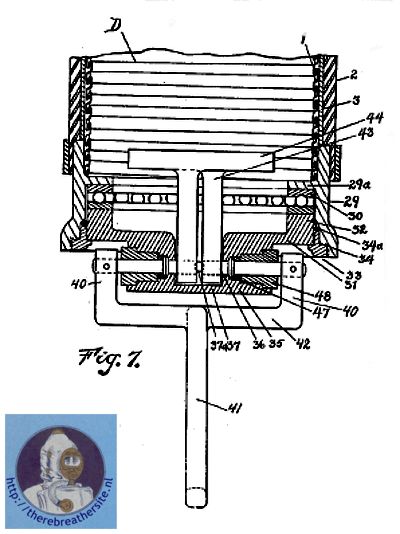

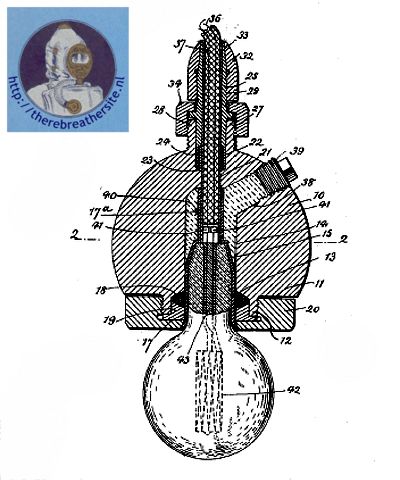

Leavitt patent for his deep sea light US patent 1611651

Time magazine 26-01-1925;

Although earth and rock are much harder substances than water, the depths of the earth have been much easier for man to reach than the depths of the water. For, although a solid is harder to penetrate initially than a fluid, once penetrated, there is a hole which offers no subsequent resistance, whereas a fluid always exerts a pressure, increasing with depth. So it happens that, although man has been down in the earth for many thousands of feet, no diver had ever until recently been down more than about 30 fathoms (180 ft.) below the surface of the sea.

But there was a Captain Benjamin Leavitt, who was not content that this paltry 30 fathoms should be set as a lower limit to his activities. In 1922 he bought a ship, the Blakely, from the Shipping Board. He fitted her out for diving and salvaging, and laid in an equipment of patent diving suits of manganese bronze (which resists salt water corrosion), with flexible parts of interlocking copper tubing and ball bearing joints, with portable air equipment, carrying a four-hour supply of oxygen and a telephone.

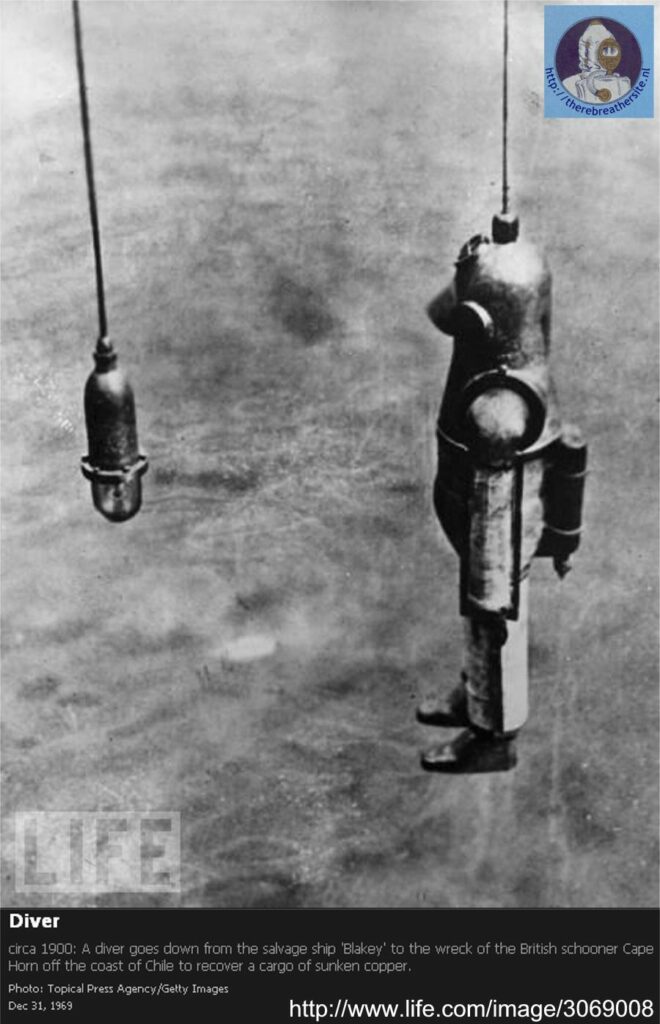

During the winter of 1923 a visit was made to the west coast of Chile. There, two miles off Pichidangui, was located the wreck of the British schooner Cape Horn, which went down in 1869 with a cargo of copper, lying in 53 fathoms (318 ft.) of water. Captain Leavitt declares that in some of his searches he went down to 60 fathoms (360 ft.). When the wreck was discovered, a difficulty came up. At 53 fathoms it was almost pitch dark; there was not enough light to work by.

So a return was made to the U. S. and special lights were, procured, incandescent vacuum lamps, with glass capable of resisting ten times; normal air pressure, made by the Westinghouse Lamp Co. With these, the expedition set out in the Blakely just a year ago. Work was begun in March. Last week, messages were received telling that $600,000 worth of copper had successfully been salvaged from the Cape Horn.

The success of this feat suggests that it may be possible to salvage between $4,000,000 and $6,000,000 in gold and valuables that sank with the Lusitania. The Lusitania, sunk by a German submarine in 1915, lies in 42 fathoms of water off the southern coast of Ireland. It opens up vistas of salvaging sunken Spanish argosies with their almost legendary treasures.

Even if the success of the present expedition has doubled the former range of practical diving from 30 to 60 fathoms, the fact remains that divers have barely scratched the epidermis on Father Neptune’s back, with its average depth of 2¼ miles.

As World War I fostered a copper shortage, Margaret C. Goodman gained attention by organizing a salvage expedition in 1917. She entered the business in order to support an invalid husband and a daughter. Goodman employed diver Benjamin Franklin Leavitt, who used a new type of diving suit capable of descending to 300 feet. The endeavor brought up more than 100 tons of copper and iron ore. Other mementos were raised from the ship, including watches, revolvers, coins predating the Civil War, bracelets, spectacles, books, ladies’ hair combs, gentlemen’s square-toed boots, slippers, handmade silk lace, baggage-room checks and door keys stamped with Pewabic’s name. No trace was found of the fabled silver-filled kegs.

After his adventures and Salvaging operations not much was heart about Mr. Leavitt anymore. I would be very pleased to know more about him, so if you have any additional information please send it to me!

Therebreathersite was founded by Jan Willem Bech in 1999. After a diving career of many years, he decided to start technical diving in 1999. He immediately noticed that at that time there was almost no website that contained the history of closed breathing systems. The start for the website led to a huge collection that offered about 1,300 pages of information until 2019. In 2019, a fresh start was made with the website now freely available online for everyone. Therebreathersite is a source of information for divers, researchers, technicians and students. I hope you enjoy browsing the content!