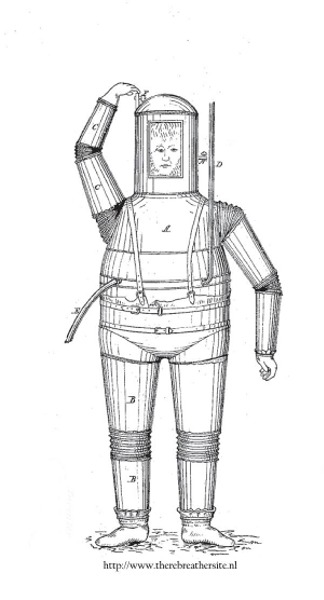

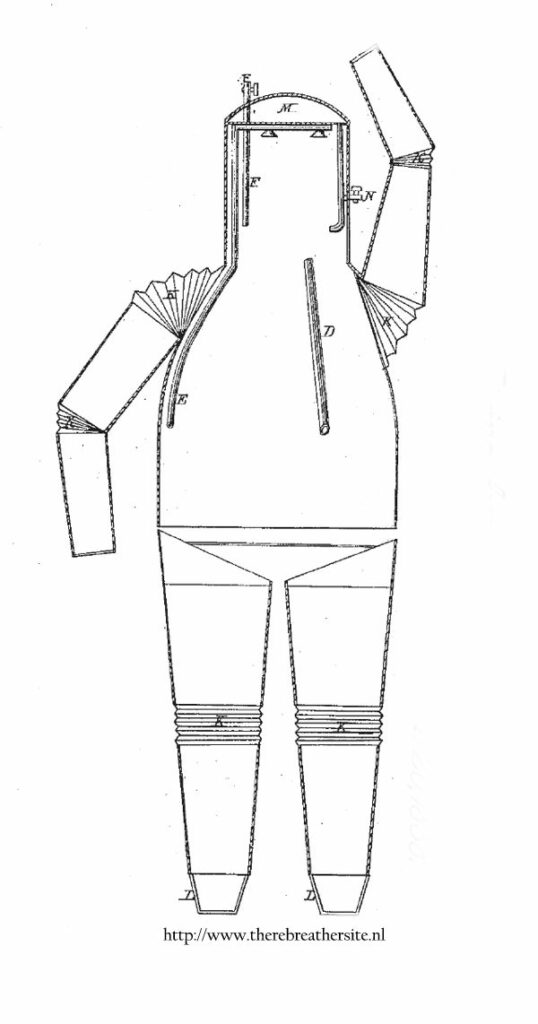

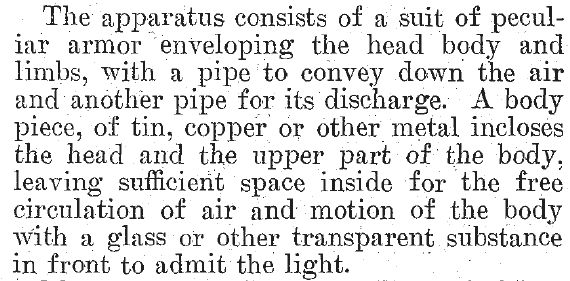

The problem with the Lethbridge gear was that the diver hardly had a possibility to move. This is something that has challenged inventors from that day on until today. The first guy that designed a suit with real joints was William Taylor in 1838. It is not sure the suit was ever actually produced. Taylor designed the joints as leather pieces with rings in the shape of a spring (known as the accordion joint). Hands and feet were covered with leather. Taylor also designed a ballast tank to the suit that could be filled with water to achieve negative buoyancy.

Taylor, 1838 (U.K.) – W.H. Taylor designed the first known armoured diving suit with articulating joints in 1838. The suit was to be surface-supplied and had accordion-like joints of spring steel, reinforced and water sealed with leather.

It is clear that Taylor did not apply the concept of Atmospheric Diving Suits. This is because the hose E in the drawing below should transport the contaminated air inside the suit to the outside. It is obvious that if the pressure in the suit was 1 bar and the ambient pressure much higher that the evacuation of the air would lead to a practical problem…

From his drawing, it seems that either Taylor had no intentions of his suit being a true atmospheric diving suit, or else had no understanding of the depth-pressure relationship. The suit appeared to exhaust directly into the surrounding water from a short hose located at the divers waist. Therefore, the interior pressure would have had to be greater than the water pressure at depth. Also, the soft cloth joints of the suit would have most likely collapsed when exposed to any considerable pressure.

suit (1838) relied on a convolute type of bellows joint using ring stiffeners and fabric

(Fonda-Bonardi and Buckley, 1967).

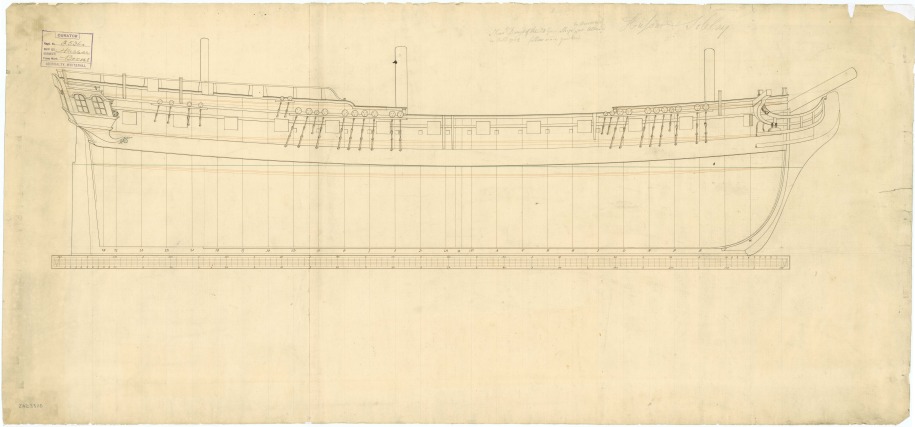

There is an article in the New York Times from 1856 describing efforts of a certain captain Taylor working in a atmospheric suit trying to find the 1.8 million treasure on board of the British frigate Hussar that sunk in 1780 carrying prisoners….This might be the same William H. Taylor….

The main problem with this type of joint was the fabric strength, which limited the suit to 150 feet (Marx, 1971).

When Admiral Sir George Brydges Rodney took his twenty ships of the line south in November, it was decided that the army’s payroll be moved to the anchorage at Gardiners Bay on eastern Long Island. On 23 November 1780, against his pilot’s better judgment, Hussar’s captain, Charles Pole, decided to sail from the East River through the treacherous waters of Hell Gate between Randall’s Island and Astoria, Queens (on Long Island). Just before reaching Long Island Sound, Hussar was swept onto Pot Rock and began sinking. Pole was unable to run her aground and she sank in 16 fathoms (96 ft; 29 m) of water. The minutes of the Royal Navy’s court martial into the loss of the frigate (record held at the National Maritime Museum, Greenwich), make no mention of any payroll money or other special cargo aboard. The document appears to be little more than an administrative formality. It suggests that whatever valuables were aboard Hussar had been off-loaded by the time of her accident.

Therebreathersite was founded by Jan Willem Bech in 1999. After a diving career of many years, he decided to start technical diving in 1999. He immediately noticed that at that time there was almost no website that contained the history of closed breathing systems. The start for the website led to a huge collection that offered about 1,300 pages of information until 2019. In 2019, a fresh start was made with the website now freely available online for everyone. Therebreathersite is a source of information for divers, researchers, technicians and students. I hope you enjoy browsing the content!